The Strategy Gap: Why Organizations Fail to Choose the Right Strategy Approach and How to Fix It

“Unfortunately, good strategy is the exception, not the rule.”

The Hidden Cause of Strategic Failure

Every organization claims to have a strategy. Many even execute theirs with precision, launching products, expanding markets, and delivering projects on time and within budget.

Yet most still fail to achieve their strategic objectives.

For decades, the convenient explanation has been poor execution. When results disappoint, leaders conclude: “The strategy was right, but implementation went wrong.”

But this explanation is comforting, not correct. Most failures stem from flawed formulation, not execution. Organizations often execute the wrong strategies perfectly. The true source of failure lies in a deeper disconnect - what I call the Strategy Gap.

This is the systematic mismatch between the strategy approach an organization needs and the one it actually uses.

When Good Execution Masks Bad Strategy

Evidence across sectors shows that between 60 and 90% of strategic plans never fully materialize. The widely held belief is that companies which manage global supply chains and flawlessly deliver billion-dollar projects somehow stumble when executing their strategies. This seems paradoxical: how can organizations so competent at execution fall short on strategy implementation? The answer lies upstream. It's not execution that’s failing, but the way strategies are initially designed.

Organizations often succeed at doing, but fail at choosing. They select the wrong strategy approaches for their environments and then execute them brilliantly.

Seven Ways Organizations Create Bad Strategies

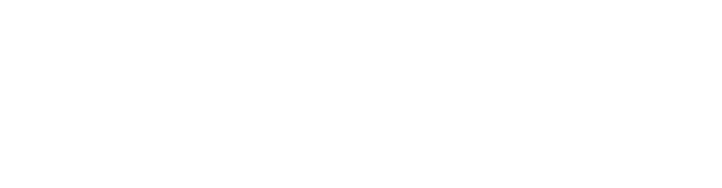

Strategic dysfunction rarely arises by accident. It follows predictable patterns that undermine effectiveness before implementation even begins. I define these as the 7 Strategy Deficits: incomplete strategy, outdated strategy, unrealistic strategy, wrong strategy, inconsistent strategy, ambiguous strategy, and performative strategy. These deficits fall into two main categories and are described in Table 1:

Awareness Deficits: Organizations produce incomplete, outdated, unrealistic, or simply wrong strategies because they lack knowledge of suitable alternatives. Put simply, they don’t know what they don’t know.

Selection Deficits: Even when they do know better, organizations ignore what they know and create inconsistent, ambiguous, or performative strategies because they default to what feels familiar or politically safe.

Incomplete strategies articulate lofty visions without the causal logic to achieve them. Outdated ones persist long after their environments have shifted. Unrealistic strategies ignore capability or resource limits. Wrong strategies misdiagnose the environment and apply solutions that don’t fit. Inconsistent strategies contain internal contradictions that undermine coherence. Ambiguous strategies leave stakeholders with conflicting interpretations. Lastly, performative strategies exist mainly to satisfy governance rituals rather than to guide real action.

These recurring failures reveal a systemic issue: organizations are not just doing strategy incorrectly; they are choosing how to strategize incorrectly.

Table 1: The 7 Strategy Deficits

The Scale of the Misalignment

Research underscores how pervasive this problem is.

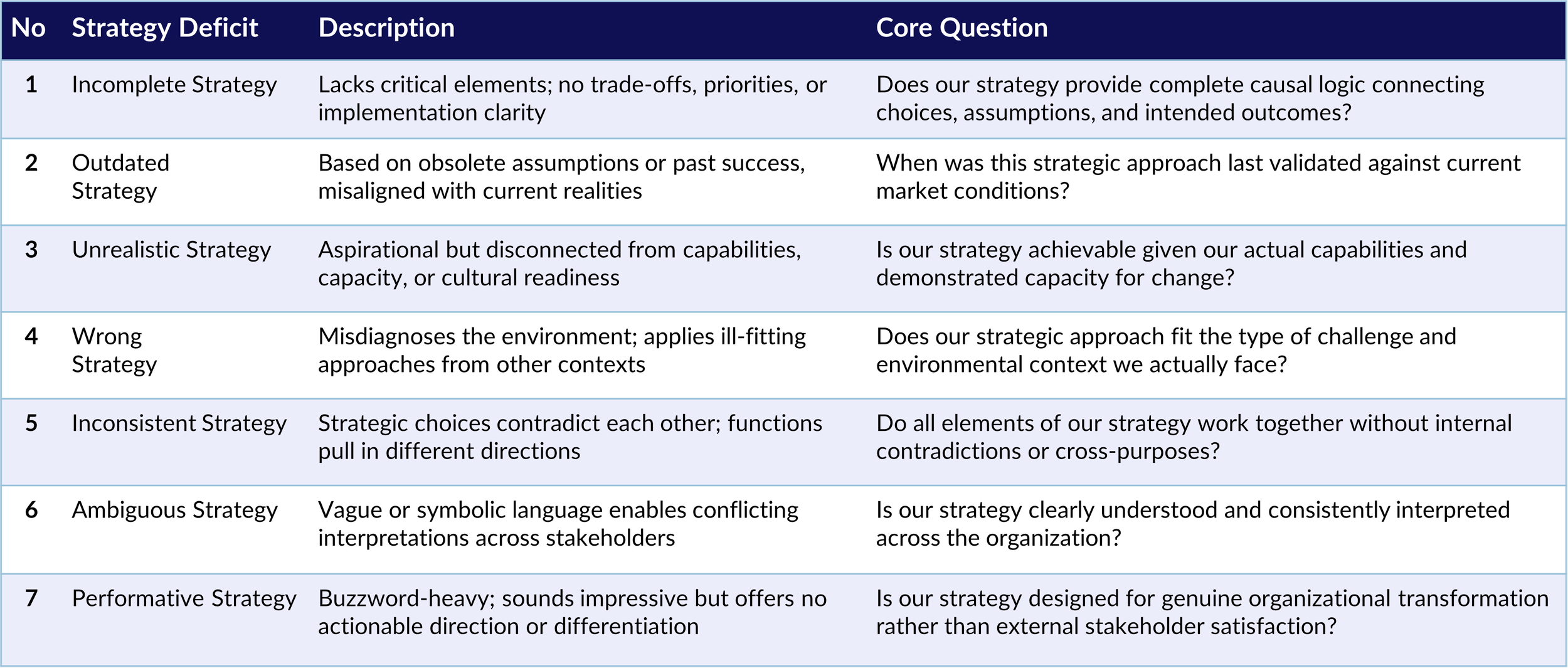

While 75% of executives acknowledge that different strategic challenges require different approaches, only 25% actually adapt their methods to the level of uncertainty and complexity they face.

This means three out of four leaders know they should tailor their approach, but don’t.

Meanwhile, the world has grown vastly more volatile. The World Uncertainty Index reached record levels in 2025, reflecting economic instability, technological disruption, geopolitical tension, ecological imperatives, and social transformation (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: World Uncertainty Index (1990-2025)

Yet strategy processes in most organizations still resemble those of the 1980s: linear, planning-based, and anchored in predictability.

The result is a widening Strategy Gap between what organizations know they should do and what they actually do.

Why Organizations Keep Choosing the Wrong Approach

As illustrated in Figure 2, even capable, well-informed leaders struggle to close this gap because three powerful levels of barriers keep pulling them back toward outdated methods.

Figure 2: The Strategy gap

I classify these as: cognitive, knowledge, and institutional barriers.

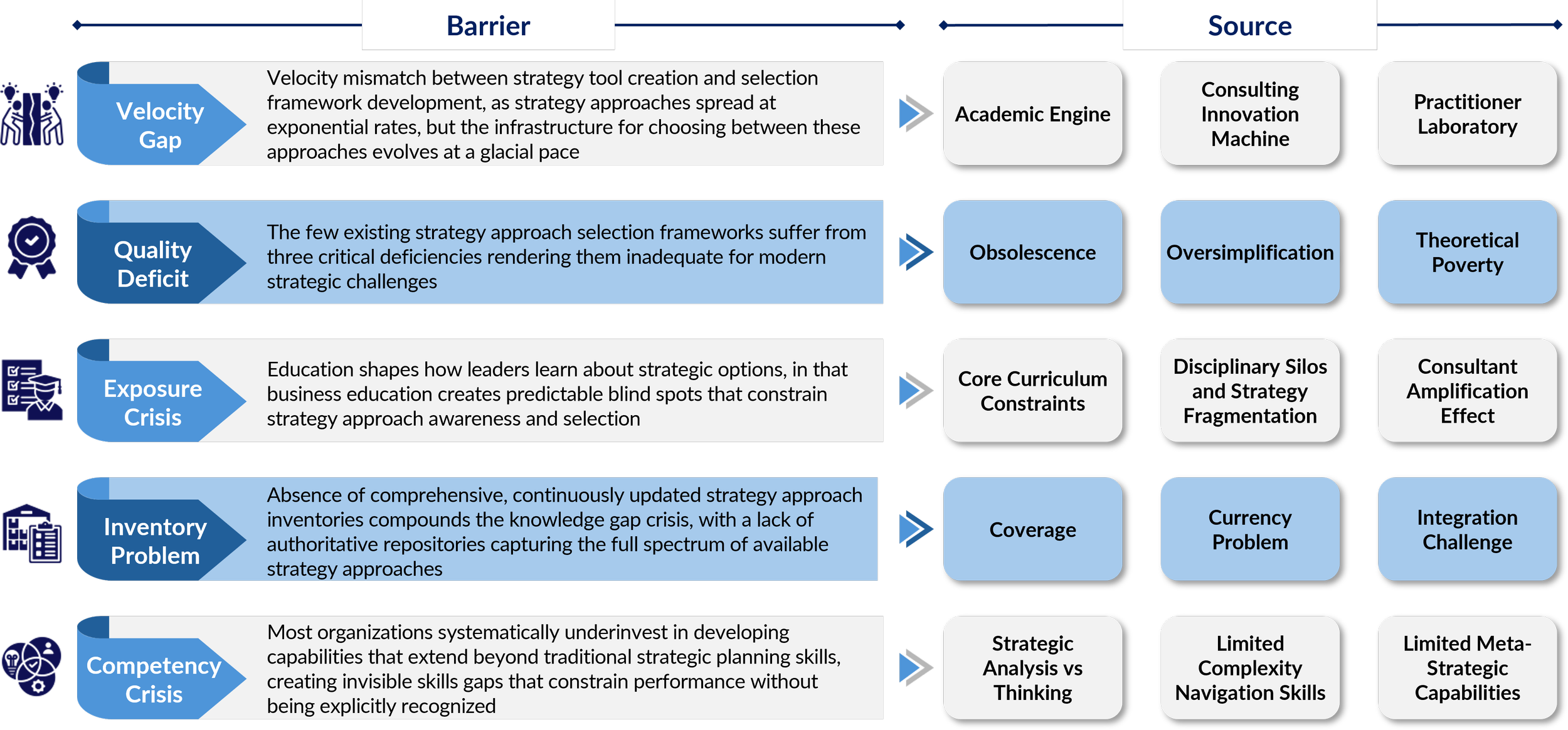

1. Cognitive Barriers – How Minds Betray Strategy

Leaders are not purely rational actors. They are influenced by predictable cognitive biases:

Familiarity bias: Defaulting to the frameworks learned in business school or consulting such as SWOT, Five Forces, and portfolio matrices, regardless of fit.

Newtonian–Cartesian thinking: Viewing the business world as linear and controllable, thereby assuming cause and effect are proportional and predictable.

Uncertainty avoidance: Resisting approaches suited for uncertain situations because overconfidence, confirmation bias, and the “ostrich effect” make leaders cling to detailed plans and forecasts even when the future is unpredictable.

Cognitive rigidity: Allowing established mental models to turn into “cognitive cages” that prevent adapting strategy when contexts change.

· Attribution Bias: Attributing success to their chosen methods while blaming failures on external factors, blocking genuine strategic learning.

These mental shortcuts make familiar tools feel safer than adaptive or experimental ones, reinforcing the very rigidity that complex environments punish. In Figure 3, I summarize the cognitive barriers and their sources.

Figure 3: The 5 Cognitive biases affecting strategy approach selection

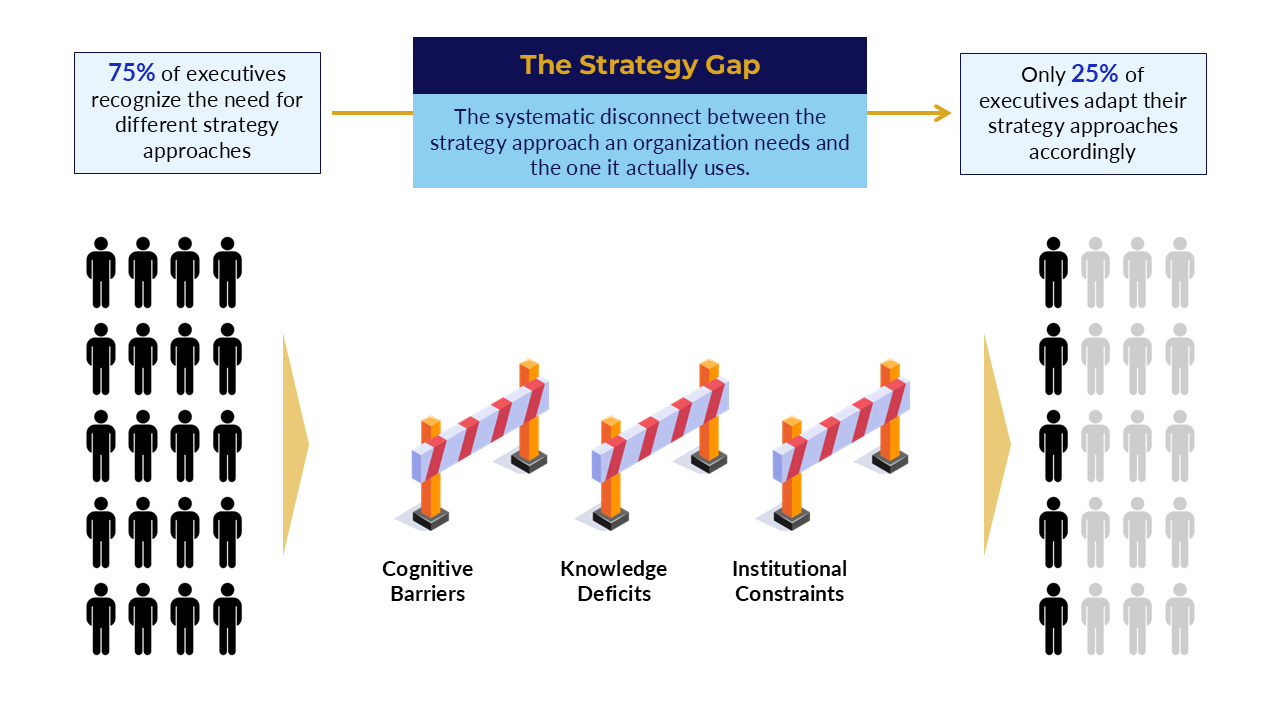

2. Knowledge Barriers – The Knowledge Gap

Over the past century, strategists have developed more than 300 frameworks, from classic competitive analysis to ecosystem and platform strategies. Yet the infrastructure for selecting between them has barely evolved.

This velocity gap, which is the speed at which new tools appear versus the slow growth of selection frameworks, creates strategic overwhelm. Faced with too many options and too little guidance, organizations either cling to what they are accustomed to, delay decisions, or chase fads.

Quality deficits in selection frameworks compound the problem, as many are obsolete since they were designed for industrial-age competition; oversimplified as they reduce complex strategic contexts to binary matrices; or theoretically poor because they are based on consulting experience rather than systematic research.

Another source of knowledge barriers is limited educational exposure. Most MBA programs cover 15 to 20 frameworks, exposing future leaders to approximately 5-7% of available methodological options. This leaves leaders unaware of modern strategic methods like sustainability transition strategies, digital-native strategies, or ecosystem orchestration models.

Moreover, the inventory problem means there is no authoritative, updated, or integrated catalogue of strategy tools. Existing lists are often incomplete, outdated, and lack guidance on fit, boundary conditions, or combination, making the abundance of options serve as noise rather than a means for clarity.

Finally, the competency crisis is a critical knowledge barrier which arises because modern strategy requires skills rarely taught in business schools: navigating uncertainty, experimenting, adapting dynamically, and mastering meta-strategic thinking, which is the ability to think about thinking about strategy.

In short, these knowledge barriers don’t just limit action, they shape what organizations believe is possible. In Figure 4, I summarize the knowledge barriers and their sources.

Figure 4: The 5 knowledge barriers affecting strategy approach selection

3. Institutional Barriers – The Organizational Cage

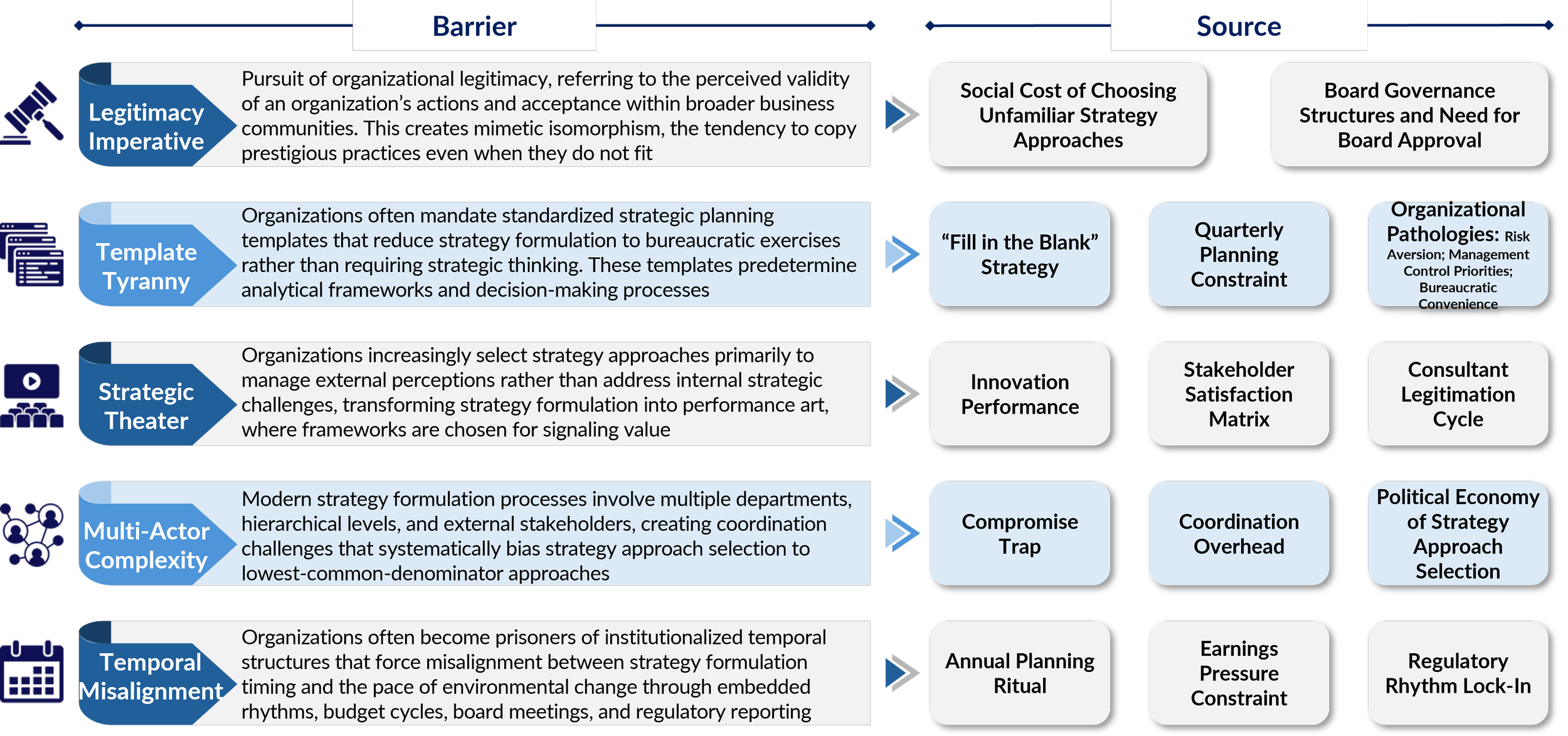

Even when leaders are cognitively aware and strategically literate, institutional pressures often prevent them from acting differently (See Figure 4):

The legitimacy trap: Boards and stakeholders favor recognizable frameworks over unconventional but contextually superior ones.

Template tyranny: Bureaucratic planning formats reduce strategy to tick-box exercises before real diagnosis.

Strategic theater: Strategy becomes performance art, acting as a signal to investors and regulators rather than a tool for real decision-making.

Multi-actor complexity: Diverse stakeholders and politics drive organizations toward lowest common denominator approaches which everyone understands over fit-for-purpose ones that require investment and learning.

Temporal misalignment: Slow planning cycles and rigid calendars crowd out adaptive, continuous strategy.

The organization itself becomes the constraint, rewarding conformity over contextual intelligence. In Figure 5, I summarize the institutional barriers and their sources.

Figure 5: The 5 institutional barriers affecting strategy approach selection

The Consequence: A Crisis of Strategic Misalignment

Across sectors, the same pathology recurs:

Private firms competing in complex ecosystems often rely on outdated, product-based rivalry models.

Public entities tackling “wicked problems” persist with linear planning.

Non-profits addressing systemic change depend on traditional goal-based approaches instead of systems thinking.

This reveals systemic misalignment, wherein sophisticated knowledge coexists with outdated behavior.

Organizations are not failing because they cannot execute; they are failing because they cannot select.

Closing the Strategy Gap

Fixing this chronic misalignment requires more than another framework. It demands a capability.

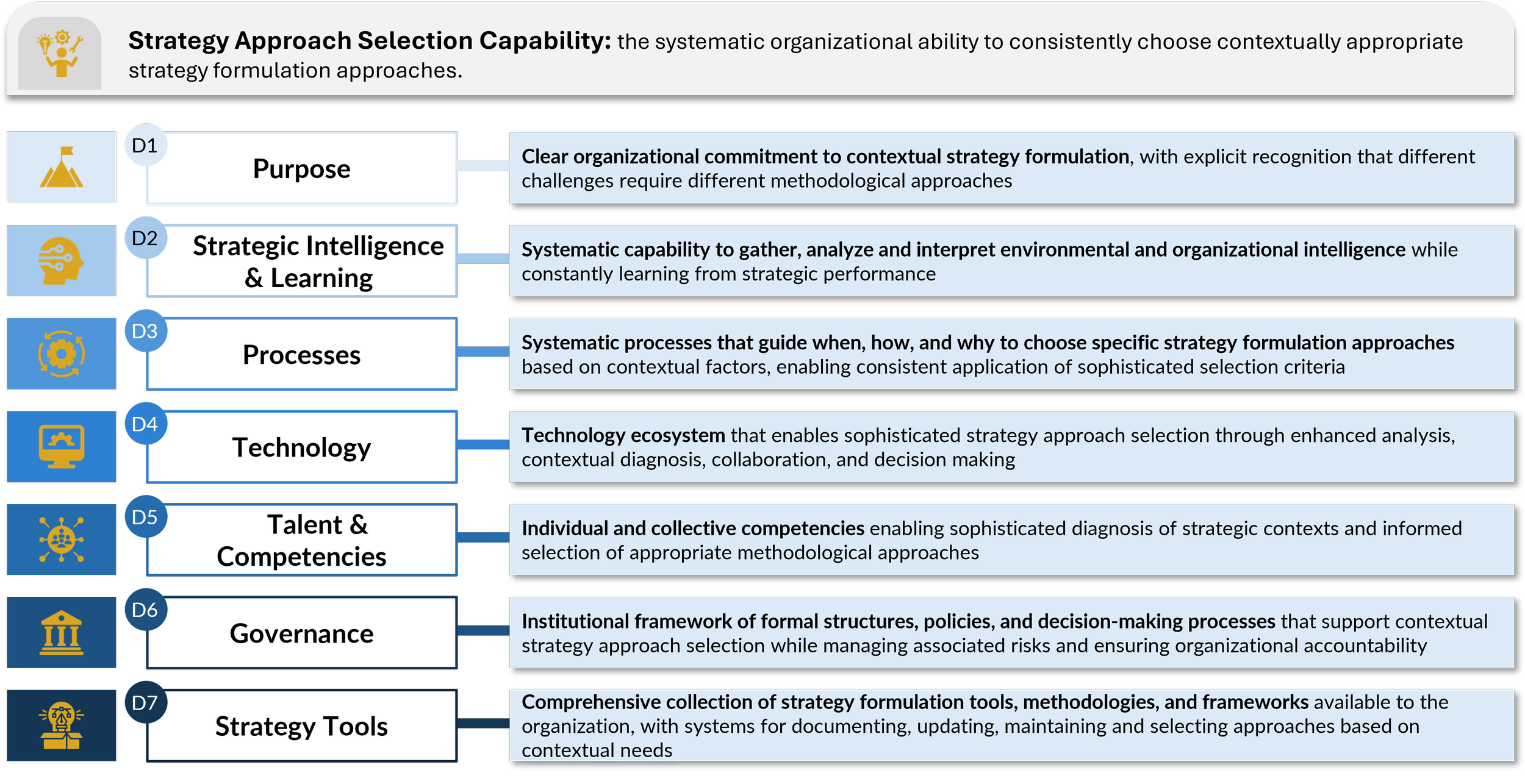

This is why I have developed the Strategy Approach Selection Capability model (SAS-C). It is the institutionalized ability to consistently choose contextually appropriate strategy formulation approaches. This capability is built across seven interdependent dimensions, each addressing specific cognitive, knowledge, and institutional barriers (See figure 6):

Purpose – A genuine commitment to contextual sophistication rather than legitimacy compliance.

Strategic Intelligence & Learning – Mechanisms to capture, analyze, and learn from the performance of different strategy approaches.

Processes – Flexible, context-responsive protocols that replace one-size-fits-all templates.

Technology – Digital platforms that enhance analysis, collaboration, and adaptive decision-making.

Talent & Competencies – Leaders trained in meta-strategic, systems, and paradoxical thinking.

Governance – Institutional structures that reward methodological diversity and contextual fit.

Strategy Tools – Curated, updated repositories linking approaches to environments and boundary conditions.

Developed together, these dimensions form the foundation of a mature organizational capability that transforms strategy from a periodic event into a continuous, adaptive, learning-based practice.

Figure 6: The Strategy Approach Capability Model

The New Strategic Imperative

In an era defined by volatility, uncertainty, and accelerating change, competitive advantage no longer lies in choosing the right strategy once and for all.

It lies in mastering how to choose the right way to strategize again and again, as conditions evolve.

Organizations that close the Strategy Gap build resilience, agility, and contextual intelligence. Those that don’t will continue executing the wrong strategies perfectly and wondering why success never follows.

About the Research

This article is based on comprehensive research from the forthcoming book "Business Strategy Formulation: The 7C Strategy Wheel" (Routledge, 2026), which introduces the most extensive strategy toolkit available, featuring seven strategic postures, 28 strategy approaches, and 59 methods derived by analyzing and synthesizing over 300 strategy tools, 25 theoretical perspectives, 2,000 literature pieces, and 200 public and private sector strategies.

About the Author

Dr. Bassil A. Yaghi is the author of “Business Strategy Formulation: The 7C Strategy Wheel”(Routledge, 2026). His research and practice focus on helping leaders build the Strategy Approach Selection Capability needed to navigate uncertainty, embrace complexity, and shape the future intelligently.